at 1716 West Sunset, I’ll be giving a reading of H.V. Chao’s fiction in the first 2012 installment of Featherless, a reading series curated by CalArts grads Andrea Lambert and Katie Jacobson. Also on the slate is the lady pictured above, on the left, Pasadena poet and performance artist Kate Durbin. I doubt that’s what she’ll be wearing, but I bet it will be something equally eye-catching. Joining us will be Camille Roy, writer and performer of fiction, poetry, and plays. I’ll be the only non-performer! Shaping up to be a spiffy evening. Stop by the Facebook event page and say Hi! Hope to see you there!

André-Marcel Adamek at Words Without Borders

January 25th, 2012 § 5 comments § permalink

Happy New Year! For various reasons, it’s been a while since I posted, but I thought I’d better get this up before the month ended, and the January issue gets archived. My translation of André-Marcel Adamek’s story “The Ark” is up at Words Without Borders, who are kicking off 2012 with an appropriately apocalypse-themed issue. It begins like this: “I shall destroy man whom I have created from off the face of Belgium…” In less than one line, the reader gets a sense of the author’s playfulness and seriousness, his ambition and ardor, his humanism and humor. It also strikes, with perfect pitch, a sort of self-deprecating chord typical to Belgian writers, aware of their country’s size and how habitually it gets passed over. Belgians are nothing if not practiced at puncturing pretension, yet for all their mockworthy dithering, they have a very strong if complicated sense of identity. You know what kind of story you’re walking into here, and it delivers: a modern-day unassuming Noah, hapless before his exacting Lord. “The Ark” overflows with love, sometimes gentle, sometimes outraged, for the people of its tiny land.

Adamek was an author with huge heart. He knew how to spin a yarn, plumb a soul, pace a scene, and wright a sentence. A consummate autodidact, he fought for and earned everything he had, wresting it from an uncharitable world with cleverness and will. When I saw him in June, the ungrateful life with which that world sometimes rewards writers had worn him to a wisp. With the Belgian government still at an impasse, and Europe itself on the verge of economic crisis, “The Ark”, first penned in the mid-90s, had come to seem timely once more, if in all the ways no one would have hoped for.

André-Marcel Adamek passed away last August.

Paul Willems in Tin House 50

December 6th, 2011 § 0 comments § permalink

“It was dawn; the sun, white as a little disk of utter ice, was perched on a red mountain. Below us, a thousand mountains! They all looked like piles of dried blood. The air was so thin, so limpid that we could see them as if they were in our hands. Not a tree, not a lake. An old scab of old blood covered the incurable wound of the world.” ~ Paul Willems, “The Horse’s Eye”

Tin House is celebrating the big five-oh issue-wise; the theme is Beauty. I’m proud to have a translation of Belgian fabulist Paul Willems rub shoulders with such goodies as:

- an essay on beauty by Marilynne Robinson,

- Aimee Bender interviewing artist Amy Cutler,

- Sonya Chung interviewing James Salter,

- Maggie Shipstead’s Tom-and-Katie-get-divorced story,

- Gavin Bowd’s translation of Michel Houellebecq,

- Eric Puchner’s youth-only future,

and lots more, so go out and pick up a copy!

I also weigh in at the Tin House blog on a sentence from James Salter’s short story “Dusk”. Like Salter, Willems applies a spare style to hint at deep and hidden feeling, but in English, I’ve not yet seen such lapidary minimalism married to fabulist content. If you like Paul Willems, look out early in the new year for my translation of his story “Cherepish” in Subtropics!

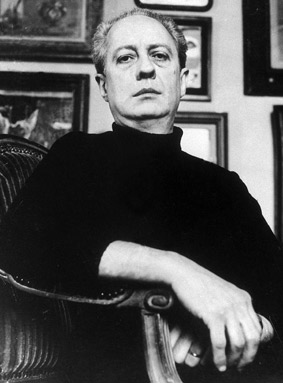

André Pieyre de Mandiargues at Words Without Borders

December 2nd, 2011 § 1 comment § permalink

My translation of André Pieyre de Mandiargues’ decadent and hallucinatory tale “The Red Loaf” is now live at Words Without Borders, which this month is running an issue on the Fantastic well worth checking out. Mandiargues’ story was reprinted in the January 1962 issue of Fiction, France’s sister publication to that venerable stateside institution, Fantasy & Science Fiction. To celebrate, I posted the cover of that issue above. Mandiargues appeared beside translations of Asimov, Pohl & Kornbluth, Belgian black humorist Jacques Sternberg (in the original, of course), and Damon Knight, the last of whom would go on to try his hand at translating French science fiction, and to co-found the Clarion Writers Workshop. The story had earlier been collected in the 1951 Soleil des loups, which took its name from a folk expression for the moon: the wolves’ sun. It was published first by Julliard, then reprinted in mass market paperback as part of the famous Fantastique imprint run by Jean-Baptiste Baronian for Belgian publisher Marabout:

Much later, it was reprinted in Gallimard’s L’Imaginaire imprint, a line of distinctive white trade paperback-sized books, for which the author produced new back cover copy.

I’m fairly proud of my translation, among the more demanding I’ve done, which in 2010 won the British Comparative Literature Association’s John Dryden Translation Prize. It was, as a result, first printed in the February 2011 issue of that Association’s journal, Comparative Critical Studies. Although more than few of Mandiargues’ novels were translated back in the day, his few stories translated into English, apart from the volume Blaze of Embers (Calder & Boyars, trans. April Fitzlyon), are hard to find and tucked like Easter eggs or afterthoughts into compendious, out-of-print anthologies. He is routinely considered one of France’s foremost writers of the fantastic in the mid 20th century, along with Marcel Schneider, Marcel Béalu, and Noel Devaulx. I first began to read him because Georges-Olivier Châteaureynaud often referred to him in interviews as a major early influence (something I see most, perhaps, in ourightly surrealistic stories like “Paradiso”).

“The Red Loaf” concerns the adventures of dandy Pluto Jedediah when his random and instinctive act of cruelty sends him on an ever-more phantasmagorical journey. Of my translation, I can only hope the author, below, would approve.

Marie-Hélène Lafon in West Branch 69

November 29th, 2011 § 0 comments § permalink

The latest issue of Bucknell’s estimable literary journal West Branch is now out, featuring among others Todd Fredson, a poet in my program at USC, and my translation of Marie-Hélène Lafon’s short story “Moles” from her 2006 collection Organs:

They never see the moles. They wonder what they’re like, and imagine them hirsute and sightless, skeletons tiny and pliable, fatty beneath plum or dark purple fur, with short, speedy feet. These feet would be webbed. The moles would have no ears and almost no eyes, just two pale slits, they’d have other means of perceiving, unusual, very underground measures, unprecedented senses. Their flesh would be soft and their supple bodies hug the curves of their dark corridors, exhausting corridors, forever rebegun, threatened by cataclysmic cave-ins, compromising fissures, floods, rampant muck, sudden mudslides, total collapse. A mole’s work is insuperable, the upkeep of corridors, the burden of the moles, their curse, is impossible. The boys can’t picture the mouths of moles, their muzzles, their snouts, words fail them, have they pink tongues, hard gray palates, have they teeth to gnaw at roots, they’d like broad flat beaver’s teeth for the moles, which are first-rate tools for earthwork but don’t fit the moles’ abbreviated shapes. The only sleep moles manage is shot through with ceaseless twitching, to sleep they gather themselves into quivering heaps, the moles are afraid, they live in fear and never for long, and then they rot in the dark earth that is their element; that much at least the boys know. They have earth in their bodies, they eat it.

Lafon’s prose is obsessive and compelling but, rather than deriving from a neurotic intellect, remains palpable and physical, rooted in a moody rurality. In such parts much is unsaid and even more unknown; she brings their full weight to bear on her characters and readers. Lafon herself hails from the Cantal, part of the region of Auvergne in the Massif Central. When asked in a 2009 interview how she got her start as a writer, she said:

“I waited a long time. I was thirty-four, it was the autumn of 1996, and I felt like I’d missed my life, stood to one side; I was like one of those cows who watch the trains go by, and cows never board the trains. I sat down at my table and began writing Liturgy, the short piece that would lend its title to my second published book. I boarded the train of my life, and have never stepped off since. Not that writing is all of life, all my life; but I will readily avow that for me writing is the epicenter of a vital earthquake, or that I never feel so intensely alive as when I write.”

Blurbs

November 23rd, 2011 § 2 comments § permalink

For a while, the ideal blurb I wanted on the book I’d write was simply, “He is right.”

Now it is, “These years later, I remember it.”

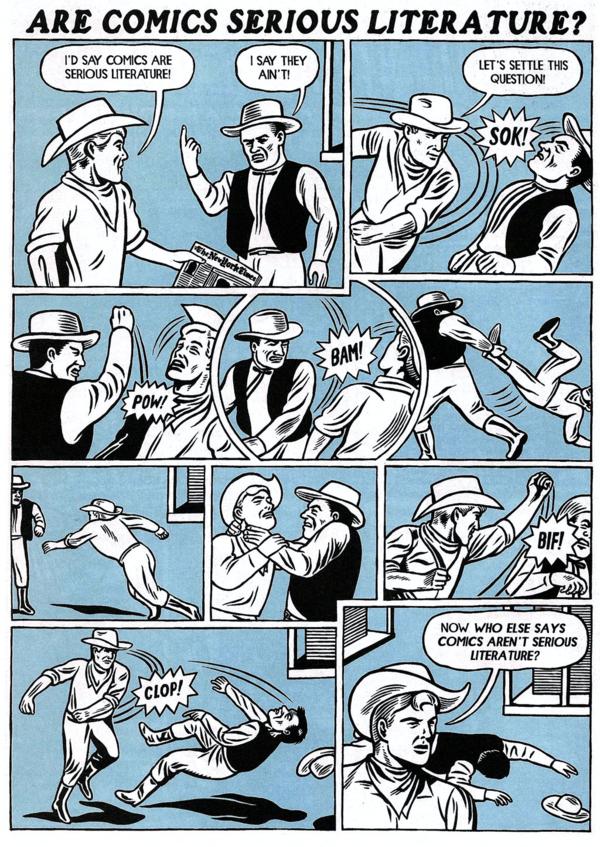

Are Comics Serious Literature?

November 22nd, 2011 § 0 comments § permalink

I’ve always loved Michael Kupperman’s work, and I loved this. I laughed. But I couldn’t suppress the niggling complaint that it seemed to want something both ways. To have the cake of seriousness and also stick out a tongue coated in cake and bits of frosting. And in this it seemed far from alone, but part of a long tradition.

Now you could read Kupperman’s strip as a takedown of the mere question “Are Comics Serious Literature?” As if the question were so ridiculous as to be beneath asking, so that the only possible reaction would be to foreground that ridiculousness, treat it with the ridicule it deserved. Or you could read this as a takedown of people who still refuse to consider comics serious literature. Either way, a dismissal is involved, but not a refutation. We are serious; take us seriously, we say. Well, why should we? they reply. And we say, Nyah, nyah. » Read the rest of this entry «

Topor Redux

November 21st, 2011 § 0 comments § permalink

Since first premiering in four parts last fall at my friend Will Schofield’s former blog of cult art and neglected books, A Journey Round My Skull, my translation of Roland Topor’s list “100 Good Reasons to Kill Myself Right Now” list sure has made the rounds. It showed up in Ryan Standfest’s Black Eye: Graphic Transmissions to Cause Ocular Hypertension anthology of comics and dark humor before moving to Will’s new site, 50 Watts. Recently, it’s turned up in Dalkey Archive’s CONTEXT (Issue #23), the leading avant-garde publisher’s critical organ of contemporary literature. There it drew a kind word first from Chad Post at Three Percent, and then the eye of Rachel Nolan of the New York Times Sunday Magazine. She picks her three favorite reasons to end it all. What are yours?

Jennifer Egan’s The Keep

November 20th, 2011 § 1 comment § permalink

Continuing the series of homely, off-the-cuff reactions to novels I’m reading in T.C. Boyle’s grad fiction workshop this semester…

I loved the description of Davis’ ghost radio on page 97. Reading it—and not instinctively interpreting it as artifice, fantastical conceit, metaphor—made me look up from The Keep and realize just how completely into its world I’d gotten, how utterly accustomed I’d become to the unique terms it sets for its own skewed reality. Our—my—impulse when confronted with fantastical contraptions is skepticism and a slight discomfort. It’s the reaction we expect and get from our guiding narrator, our mediator between novelistic reality and our own (in this case, Ray). How (seriously) are we meant to take something patently insane? Pile on the impossible events, inventions, and a tacit bargain gets struck, the entire story ascends, floating over incredulity on its way to allegory, and jettisoning some immediacy on the way. But that’s not the tack The Keep takes. Even Ray’s skepticism is somehow muted, and shades into a befuddled willingness, a cautious acceptance, the why-not? shrug of a man with nothing to lose. The thrilling part was that I was ready to take the ghost radio on similar terms—that is, at face value. If Davis claimed it was a ghost radio, who knew? Maybe it was. The novel had somehow prepared me for this: to accept the cockamamie as cold fact. But how? By fostering an atmosphere of uncertainty? Or, within this atmosphere of uncertainty, this narrative intangibility where anything might happen, maintaining a scrupulous, hard-nosed realism? Because if anything was true, it was that at page 97, I had little idea what would happen next. » Read the rest of this entry «

What’s going on in Châteaureynaud-land?

November 8th, 2011 § 0 comments § permalink

The Christian Science Monitor put Georges-Olivier Châteaureynaud’s A Life on Paper at #3 on their “10 Novels in Translation You Should Know” list. So it’s not a novel, but hey! I appreciate it.

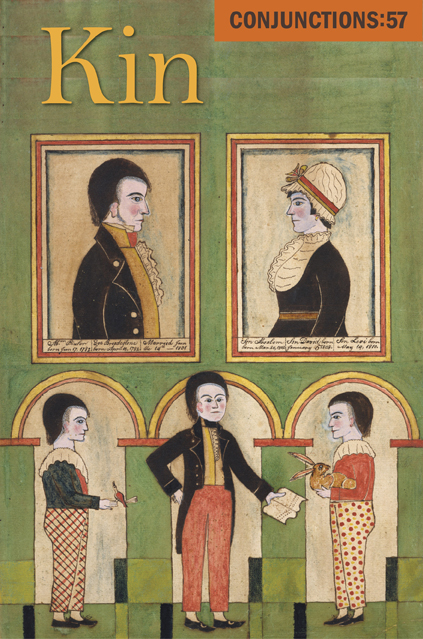

And today I just got the comps for issue 57 of Conjunctions, themed Kin:

I am proud to have a translation of Châteaureynaud’s “Buddy” in this issue. Originally slated for the story collection, this satire of King Kong and Nazi Germany was cut at the last minute for fear of legal reprisals from Warner Brothers, or the tangled brood still deathlocked with the studio in a long struggle over rights to such diverse items as character names and merchandising rights. The story’s a gem–please check it out–and forms a couple with Châteaureynaud’s other King Kong story, “The Denham Inheritance,” which appeared in Postscripts 20/21 from PS Publishing in Spring 2010.

Seriously, check out the authors here: Karen Russell, Rick Moody, Octavio Paz, Joyce Carol Otes, Ann Beattie, Can Xue, Micaela Morrissette… plus, best of all, two good friends:

- Scott Geiger, with “Quality of Life in Switzerland” and

- Elizabeth Hand, with “Uncle Lou”

Can’t wait to read!