August 26th, 2012 § § permalink

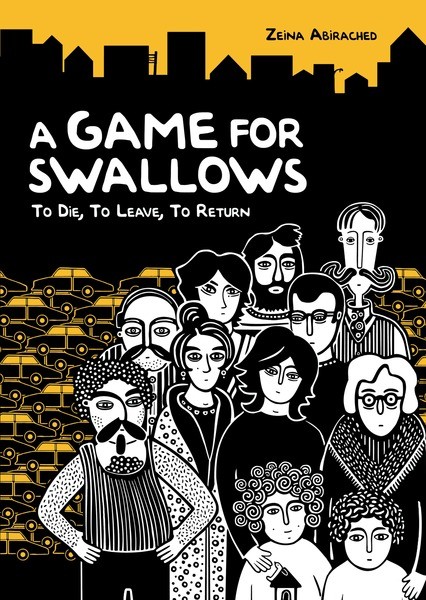

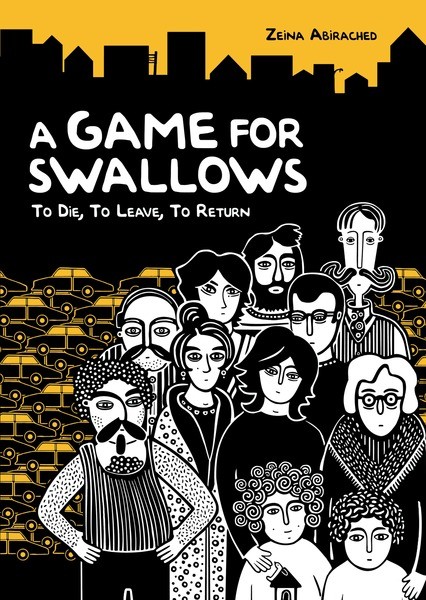

from Publishers’ Weekly for Zeina Abirached’s A Game for Swallows:

“Abirached’s B&W inks offer a stark contrast in hard, geometric patterns that make images at once abstract and fully representative of her childhood memories. The characters, despite their cartoonish nature, show a variety of emotions, and Abirached’s gift for pacing makes tense moments appropriately full of anxiety. It is as often the space she leaves empty as the drawings themselves that tell the story—and each detail offered provides insight into the horrors of growing up in a war zone. A winner for young readers and adults alike.”

August 23rd, 2012 § § permalink

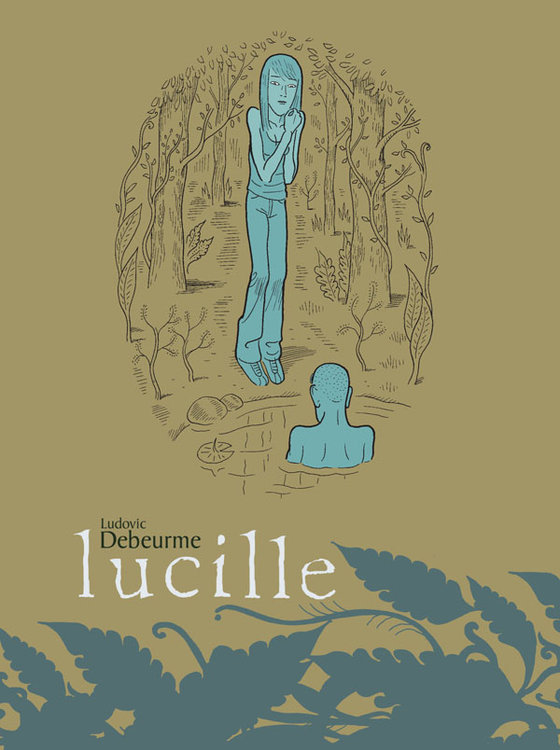

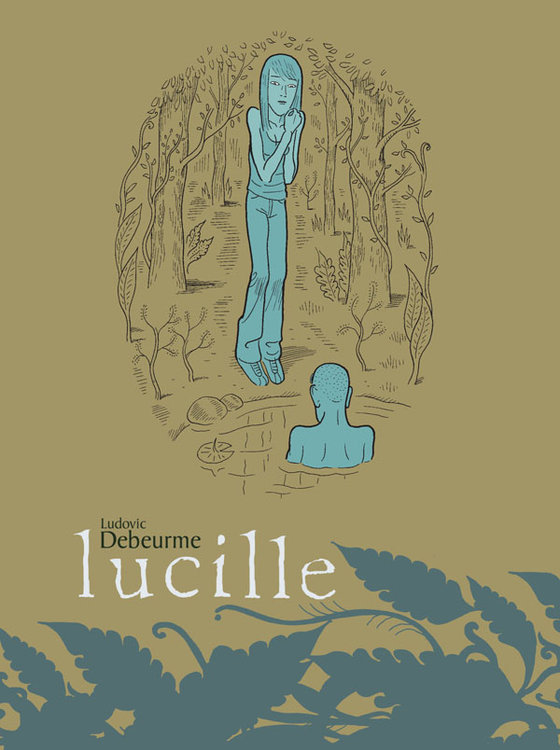

This year’s Ignatz nominations are in, up for Outstanding Story is Ludovic Debeurme’s U.S. debut Lucille, which came out last year from Top Shelf to stunning reviews! I recently wrote a bit about translating it and its forthcoming sequel Renée at Weird Fiction Review.

The Ignatz Awards, named for the brick-wielding mouse in George Herriman’s classic strip Krazy Kat, are intended to recognize outstanding achievements in comics and cartooning by small press creators or creator-owned projects published by larger publishers. Recipients are determined by attendees at Bethesda’s annual Small Press Expo (SPX), a weekend convention and tradeshow showcasing creator-owned comics. Nominations are made by a five-member jury of comic book professionals.

August 10th, 2012 § § permalink

After being left untouched for nigh on a year, the Translations page (see lower left for link) is now up to date at last, thanks to the efforts of my dog, who is very tired from all that typing.

August 2nd, 2012 § § permalink

In honor of the late enigmatic nomad and wandering guerrilla of art, I’d like to share the opening to a book that will probably never be translated: Chris Marker’s first and only novel. Le cœur net (mystifyingly rendered as The Forthright Spirit on Wikipedia and in The Washington Post, but probably someone knows something I don’t) takes its title from a standard expression that has been a perennial thorn in translators’ sides, en avoir le cœur net. Usually “mind†is swapped in for cœur, or heart, resulting in “to be clear in one’s mind†or “get peace of mind†about something, though it has been translated more colloquially as “to get to the bottom†of something, or “to clear [the matter] up.†Another tack is to go with net, or clean, and “make a clean breast†of things.

Marker’s novel was first published by the prestigious literary house Le Seuil in 1949; he was also the editorial director for their Petite Planète imprint. Though it has since been reprinted at least twice, by Le Club Français du Livre and La Petite Ourse, Marker himself disowned and suppressed it (which is why I venture that no translation of it will be legally published anytime soon). Concerning as it does the reminiscences of Agyre, the ghost of a former pilot, it’s hard to read now without hearing echoes (heralds?) of Marker’s most famous work, La Jetée. Probably its most often quoted line is the eerily apt: “Dying is, at most, the opposite of being born. The opposite of living remains to be found.â€

“An accident is nothing, quite precisely nothing. There’s the moment before, when the plane leaves the runway, when a certain quality of silence around it, a certain anticipation in the light, hides it from movement, a petrifying fountain (like an angel pressed for time who plucks the souls from men, like the blindfold placed on a condemned man seconds before death)—and the moment after, when the plane is no more than a dart in the ground, a fried grasshopper, a cross… Between the two, nothing.

You’re amazed to have seen it coming. You know, you’re ready to swear that the moment the plane took off you expected the accident, and all the rest just met your expectations. And yet you didn’t move, or make a sound. The accident is a fakir: it lulls you to pull off its feats. Sometimes all you have to do is say something, reach out your hand, to ward off its work.â€

August 1st, 2012 § § permalink

(I’ve been sitting on these thoughts for some time, pending more precise, perfected phrasing that might give them greater clarity, but as they dovetail somewhat with Lucas Klein’s recent, lucid, and considered reflections on reviewing translation, especially his concern that foreign work be evaluated in a domestic context, I thought I’d post them anyway, because hey, what’s a blog if not a place for rough drafts?)

I have never much liked the idea of literary translation as performance. The comparison, usually musical, is unimpeachable at heart: a performance is an individual rendition of an existing score, as is a translation of a text. (Rendition, we say, to avoid using that slippery and too closely related word, interpretation.) I am too literal-minded, however, and like my metaphors to map better. The score is the original text, the composer the author, and the performer the translator. So far, so good. The piece as performed—not as written—is the translation, and here I begin to run into trouble.

The idea has obvious merits. It allows for, and even goes some way toward explaining, the variety of translations that may arise from the same material. To do so, it prizes expressiveness. Translation is artistic, subjective, even personal. If we hold that the translator’s highest good is sympathy to spirit over letter, then like a performer, the translator’s dual duties are fidelity and enchantment: in bringing out the essential qualities of a piece, to make it captivating for a public that either does not read music or has no access to the score before hearing it played (in both cases, like most of the readership in a country where a translation is published). In this scheme, musical notation is the source language—but how reductive, really, for what language is so universal and invariable? There is no wrong way, beyond the merely technical, to read music—but there are many wrong ways to play it.

The performance differs from the original in the tools at a performer’s disposal: vicissitudes of tempo, emphasis, intonation, volume, exploited within some elastic yet definitely bounded allowances of taste and tradition. Perhaps the source language is something more ethereal then, something approaching a cultural-historical understanding. But mustn’t a translator also possess such understanding in addition to understanding the source language? And doesn’t any understanding, whether of language or context, reside like apperceptions of enchantment or essential qualities, in the translator’s mind? It seems this metaphor leaves out language—not necessarily by dint of prioritizing performer and performance, but nevertheless—and in doing so, leaves out much of what distinguishes translation as an activity: the negotiation between two systems.

And what, in the reverse mapping, is a musical instrument? A score often stipulates the instrument, or is even composed with it in mind, for instruments, like languages, have their particularities; no source material stipulates any eventual target language. If a translator’s instrument is language, what is left for the original language to be? If an instrument is some externalization of what a performer brings to a piece, what part of the understandings listed above does a translator externalize? An instrument is hardly a typewriter or a bilingual dictionary. If the only kind of performance to accurately map translation is an attempt to play music meant for one instrument on another, then what was once metaphor quickly becomes tautology. » Read the rest of this entry «