November 29th, 2011 § § permalink

The latest issue of Bucknell’s estimable literary journal West Branch is now out, featuring among others Todd Fredson, a poet in my program at USC, and my translation of Marie-Hélène Lafon’s short story “Moles” from her 2006 collection Organs:

They never see the moles. They wonder what they’re like, and imagine them hirsute and sightless, skeletons tiny and pliable, fatty beneath plum or dark purple fur, with short, speedy feet. These feet would be webbed. The moles would have no ears and almost no eyes, just two pale slits, they’d have other means of perceiving, unusual, very underground measures, unprecedented senses. Their flesh would be soft and their supple bodies hug the curves of their dark corridors, exhausting corridors, forever rebegun, threatened by cataclysmic cave-ins, compromising fissures, floods, rampant muck, sudden mudslides, total collapse. A mole’s work is insuperable, the upkeep of corridors, the burden of the moles, their curse, is impossible. The boys can’t picture the mouths of moles, their muzzles, their snouts, words fail them, have they pink tongues, hard gray palates, have they teeth to gnaw at roots, they’d like broad flat beaver’s teeth for the moles, which are first-rate tools for earthwork but don’t fit the moles’ abbreviated shapes. The only sleep moles manage is shot through with ceaseless twitching, to sleep they gather themselves into quivering heaps, the moles are afraid, they live in fear and never for long, and then they rot in the dark earth that is their element; that much at least the boys know. They have earth in their bodies, they eat it.

Lafon’s prose is obsessive and compelling but, rather than deriving from a neurotic intellect, remains palpable and physical, rooted in a moody rurality. In such parts much is unsaid and even more unknown; she brings their full weight to bear on her characters and readers. Lafon herself hails from the Cantal, part of the region of Auvergne in the Massif Central. When asked in a 2009 interview how she got her start as a writer, she said:

“I waited a long time. I was thirty-four, it was the autumn of 1996, and I felt like I’d missed my life, stood to one side; I was like one of those cows who watch the trains go by, and cows never board the trains. I sat down at my table and began writing Liturgy, the short piece that would lend its title to my second published book. I boarded the train of my life, and have never stepped off since. Not that writing is all of life, all my life; but I will readily avow that for me writing is the epicenter of a vital earthquake, or that I never feel so intensely alive as when I write.”

November 23rd, 2011 § § permalink

For a while, the ideal blurb I wanted on the book I’d write was simply, “He is right.”

Now it is, “These years later, I remember it.”

November 22nd, 2011 § § permalink

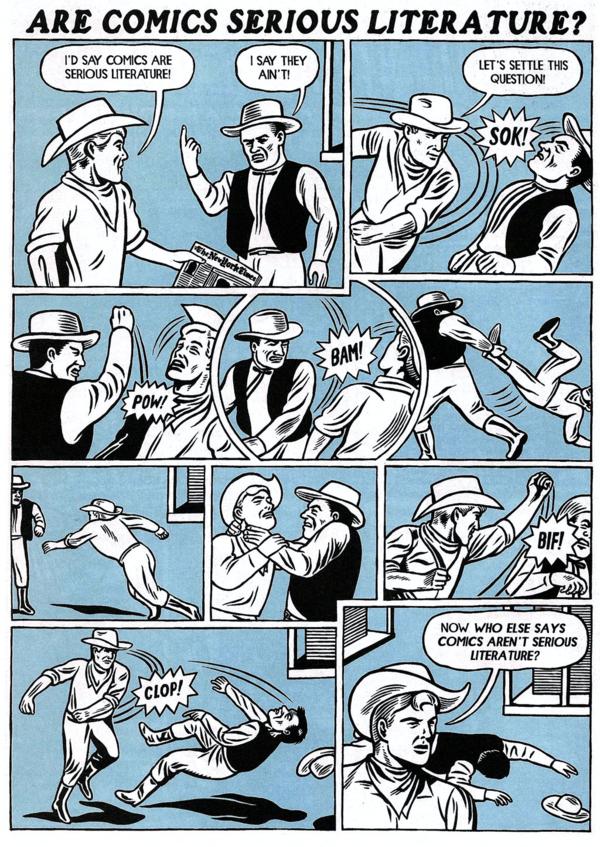

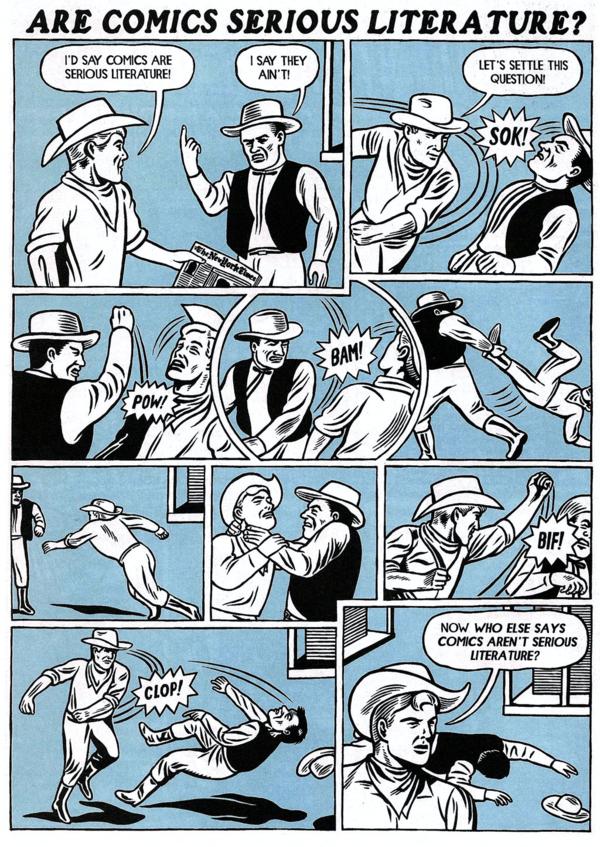

I’ve always loved Michael Kupperman’s work, and I loved this. I laughed. But I couldn’t suppress the niggling complaint that it seemed to want something both ways. To have the cake of seriousness and also stick out a tongue coated in cake and bits of frosting. And in this it seemed far from alone, but part of a long tradition.

Now you could read Kupperman’s strip as a takedown of the mere question “Are Comics Serious Literature?” As if the question were so ridiculous as to be beneath asking, so that the only possible reaction would be to foreground that ridiculousness, treat it with the ridicule it deserved. Or you could read this as a takedown of people who still refuse to consider comics serious literature. Either way, a dismissal is involved, but not a refutation. We are serious; take us seriously, we say. Well, why should we? they reply. And we say, Nyah, nyah. » Read the rest of this entry «

November 21st, 2011 § § permalink

Since first premiering in four parts last fall at my friend Will Schofield’s former blog of cult art and neglected books, A Journey Round My Skull, my translation of Roland Topor’s list “100 Good Reasons to Kill Myself Right Now” list sure has made the rounds. It showed up in Ryan Standfest’s Black Eye: Graphic Transmissions to Cause Ocular Hypertension anthology of comics and dark humor before moving to Will’s new site, 50 Watts. Recently, it’s turned up in Dalkey Archive’s CONTEXT (Issue #23), the leading avant-garde publisher’s critical organ of contemporary literature. There it drew a kind word first from Chad Post at Three Percent, and then the eye of Rachel Nolan of the New York Times Sunday Magazine. She picks her three favorite reasons to end it all. What are yours?

November 20th, 2011 § § permalink

Continuing the series of homely, off-the-cuff reactions to novels I’m reading in T.C. Boyle’s grad fiction workshop this semester…

I loved the description of Davis’ ghost radio on page 97. Reading it—and not instinctively interpreting it as artifice, fantastical conceit, metaphor—made me look up from The Keep and realize just how completely into its world I’d gotten, how utterly accustomed I’d become to the unique terms it sets for its own skewed reality. Our—my—impulse when confronted with fantastical contraptions is skepticism and a slight discomfort. It’s the reaction we expect and get from our guiding narrator, our mediator between novelistic reality and our own (in this case, Ray). How (seriously) are we meant to take something patently insane? Pile on the impossible events, inventions, and a tacit bargain gets struck, the entire story ascends, floating over incredulity on its way to allegory, and jettisoning some immediacy on the way. But that’s not the tack The Keep takes. Even Ray’s skepticism is somehow muted, and shades into a befuddled willingness, a cautious acceptance, the why-not? shrug of a man with nothing to lose. The thrilling part was that I was ready to take the ghost radio on similar terms—that is, at face value. If Davis claimed it was a ghost radio, who knew? Maybe it was. The novel had somehow prepared me for this: to accept the cockamamie as cold fact. But how? By fostering an atmosphere of uncertainty? Or, within this atmosphere of uncertainty, this narrative intangibility where anything might happen, maintaining a scrupulous, hard-nosed realism? Because if anything was true, it was that at page 97, I had little idea what would happen next. » Read the rest of this entry «

November 8th, 2011 § § permalink

The Christian Science Monitor put Georges-Olivier Châteaureynaud’s A Life on Paper at #3 on their “10 Novels in Translation You Should Know” list. So it’s not a novel, but hey! I appreciate it.

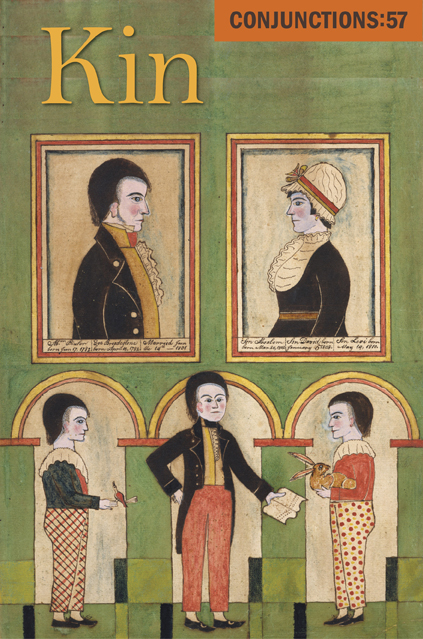

And today I just got the comps for issue 57 of Conjunctions, themed Kin:

I am proud to have a translation of Châteaureynaud’s “Buddy” in this issue. Originally slated for the story collection, this satire of King Kong and Nazi Germany was cut at the last minute for fear of legal reprisals from Warner Brothers, or the tangled brood still deathlocked with the studio in a long struggle over rights to such diverse items as character names and merchandising rights. The story’s a gem–please check it out–and forms a couple with Châteaureynaud’s other King Kong story, “The Denham Inheritance,” which appeared in Postscripts 20/21 from PS Publishing in Spring 2010.

Seriously, check out the authors here: Karen Russell, Rick Moody, Octavio Paz, Joyce Carol Otes, Ann Beattie, Can Xue, Micaela Morrissette… plus, best of all, two good friends:

Can’t wait to read!

November 5th, 2011 § § permalink

Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s big top of weird wonders has premiered! Your one-stop shop for weird in all its stripes, colors, shapes, and textures, from comics and interviews to fiction and reviews. This is the hub the wheel of weird revolves around, the bale-eyed brain and source of all things tentacular. Check out the bottomless goodie bag of round tables, exclusives, podcasts, and previews, and stop by my translation of Belgian horror writer Thomas Owen’s story “Kavar the Rat” now in print for the first time after its podcast debut at Pseudopod!

The cauldron bubbleth over: there will be “new conÂtent on WFR every week day through the end of the year, excludÂing holÂiÂday weeks, and then to either conÂtinue on a daily basis or post disÂcrete “issues†of the site. Keep the broth abrew, and hit that PayPal button while you’re at it: the site is currently running on donaÂtions only. I am proud to announce that I will joining the site as a regular guest columnist, so please feed us weirdlings! Don’t let us go hungry! A ha’penny will do! (If you haven’t got a ha’penny then C-thul-hu!)

Next week’s features include:

—An extended excerpt from China Mieville’s afterÂword to The Weird

—Three feaÂtures on Alfred Kubin, the first author in The Weird, two by Paul Smith

—The next episode of Leah Thomas’s web comic and an interÂview with the creÂator

—An excluÂsive feaÂture from Jim Kelly and John Kessel on their Kafkaesque antho

–InterÂviews with Thomas LigÂotti and Margo LanaÂgan

–Video covÂerÂage of the extraÂorÂdiÂnary Cute & Creepy art show

–FicÂtion from JefÂfrey Thomas: “The Forkâ€

November 5th, 2011 § § permalink

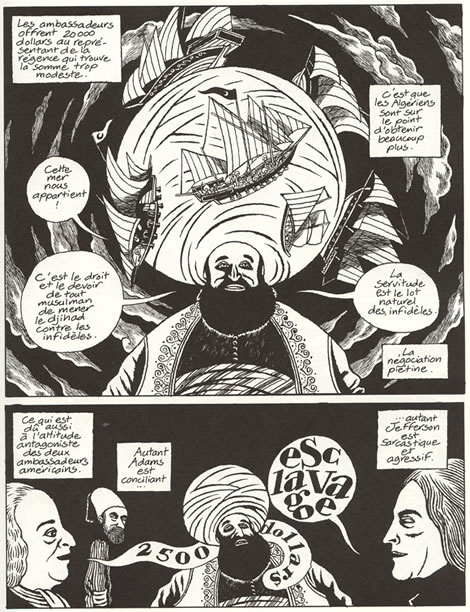

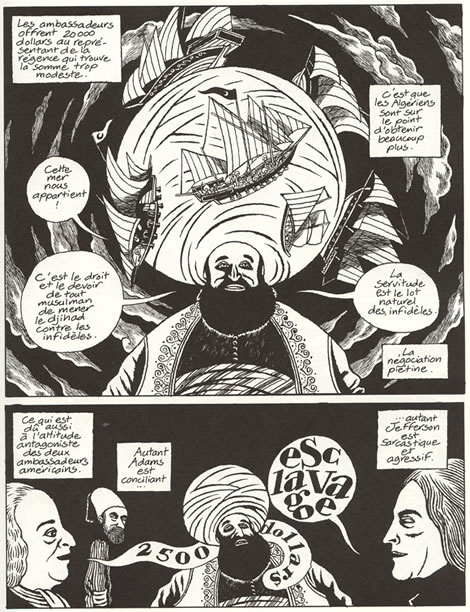

There’s been some buzz on the interwebs already among comics fans in the know about the first of David B.’s two-volume history of U.S.-Middle Eastern relations, Best Enemies (Les Meilleurs Ennemis: une histoire des relations entre les Etats-Unis et le Moyen-Orient). Co-written with Jean-Pierre Filiu, Book One, which covers 1783-1953, was just published this year by Futuropolis, Gallimard’s powerhouse indie comics arm, which has brought out most of David B.’s post-L’Association work. Paul Gravett, Britain’s brilliant indie comics pundit, posted a nice appreciation of it in a timely 9/11 blogpost. Beginning with a retelling of the tale of Gilgamesh, this first volume runs from the naval wars with the Barbary pirates through the WWII machinations that cemented the Saudi-U.S. bond. That’s Jefferson in the page above, lecturing Sidi Haji Abdul Rahman, Tripoli’s envoy, on slavery. The amazing little British publisher Self-Made Hero will be bringing the book to the U.S. and U.K.

Most stateside mentions of the book were tied to reviews of Craig Thompson’s Habibi, usually compared to David B.’s The Armed Garden (the two works probably shouldn’t be compared, since they have very different aims, though David B. largely dodges the accusations of Orientalist slumming currently leveled at Thompson by being at once more narratively inventive and aesthetically hermetic). I’ll say it now, and I’ll say it here, since only sixty people read this blog a few times a year: thank God more David B. is coming to the States. As both an artist and writer, David B. has been one of the greatest talents on the French comics scene for the last twenty years, and it’s about time he emerged from the shadow of artists he influenced (Thompson) or taught to draw (Satrapi). Because of the weird time gap it can often take for most foreign artists to make it in America, David B. will probably come to seem reminiscent of artists who couldn’t have existed without him. Let me grouch about this some more. Part of this is almost certainly childish “I knew about this first” pride, or a hipster grumble. I was into David B. before what I hope will be the era of his universally acknowledged cool.

David B.’s U.S. career took a big hit after his masterpiece of a memoir Epileptic, mismarketed by Pantheon in the wake of Persepolis, tanked. For a while the only David B. you could find were short pieces in Fantagraphics’ Mome, a handsome organ that mostly preaches to a faithful choir. But his talent is such that recognition proved inevitable, and the awareness begun back then seems to be turning into a groundswell. A few years ago, NBM put out a book of his dream diairies, Fantagraphics did The Armed Garden (collecting some pieces that had already appeared in Mome) and The Littlest Pirate King (Roi Rose, which David B. adapted from a Pierre MacOrlan short story). Self-Made Hero did his two-book story on Italian poet Gabriele d’Annunzio, Black Paths (Par les chemins noirs). In other words, David B. was poised for a comeback. Problem for me was that these fine and reputable publishing houses had longstanding traditions of working with certain translators already (NBM with Joe Johnson, and for Fanta, co-founder Kim Thompson). Edging in an excerpt from an early David B. piece, A Bomb in the Family (La bombe familiale), at Words Without Borders was the best I could manage. There’s almost nothing the man’s done I don’t like, from standalones to dream diaries to unfinished series to collaborations: Le Tengû carré, La Lecture des ruines, Le Cheval blême, Les Complots nocturnes, Les Chercheurs de trésors, Urani, Le Capitaine écarlate, Hiram Lowatt et Placido, Terre de feu… A review of Thomas McGuane in the New York Times once claimed he “makes the page, the paragraph, the sentence itself a record of continuous imaginative activity.” Replace paragraph with panel, sentence with line, and that applies to David B. His art roils, unrestful, in constant ferment and turmoil, merging idea and reality, inhabiting a constant lucid metaphorical space, at once iconic and dynamic, ritualized and alive, its bold solids and intricate geometries making full use of a static medium.

So, long story short, I’m glad to be working on him at last, and hope he’ll be emerging the shadows this time, into rightful recognition at last as the major figure and influence he is.

November 2nd, 2011 § § permalink

and nominees, all of whom can be found here, especially

- Kate Bernheimer & Carmen Gimenez Smith, editors of the new fairy tale anthology My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me. Kate’s Fairy Tale Review remains a flagship in the field.

- my Clarion teacher Liz Hand, who took Best Novella with “The Maiden Flight of McCauley’s Bellerophon†(in Stories: All-New Tales), part of which she read to us two years ago at Mysterious Galaxy in San Diego, during the Workshop,

“As you may see, I am not here, but just now, at this exact moment I am in Rosario, very far away from here but thinking of you all, and I wonder: what are they thinking now? Are they happy to be here? Yes.I know you are, and then, of course, I am happy too. And I feel immensely grateful. This Award is very important to me. It comes to my hands at the right moment. At eighty–three years old, I can count so many blessings: my husband, my sons, my daughter, my grandsons and my granddaughter, and my accomplices: the words I put in my thirty books of narrative. As Jorge Luis Borges once said, I am condemned to Spanish words. And I am trying to say in my poor English that I feel happy and joyful and that I send you my love and my gratitude. Thank you.”