(In July 2009, Words Without Borders published an excerpt from Jochen Gerner’s critical nonfiction comic Contre la B.D.—specifically, part of the chapter entitled “Against Art.†It’s a thought-provoking piece that’s gotten some nice notice around the web. There’s a good essay available in French and English on it at du9, a site devoted to the 9th art, comics.

In the “Archival†rubric of this blog, which I’m launching with this entry today, I’ll be returning for brief considerations of works I’ve already translated, for any number of reasons: to provide greater context on a piece, to say something I wish I could have at the time, to publish thoughts edited out of other articles, to share things I’d now do differently, to find a home for musings rejected elsewhere. Orphan thoughts, or stragglers.)

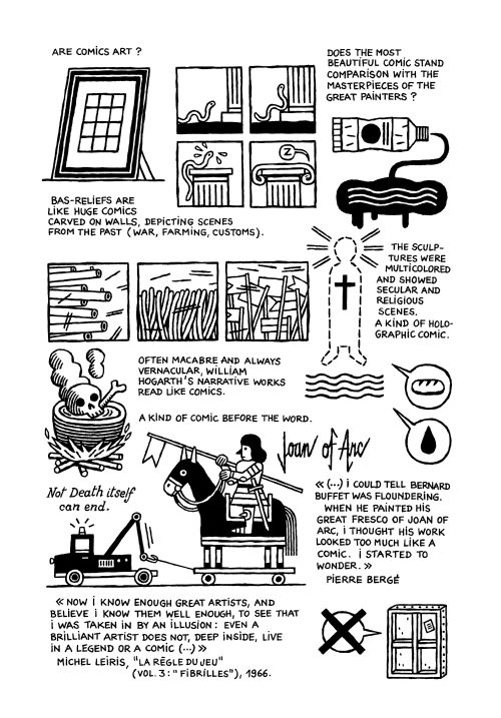

Jochen Gerner’s book-length comics essay Against Comics (L’Association, 2008) could plausibly be read as part of what Canadian comics scholar Bart Beaty calls the “postmodern project†of the “contemporary European comic book avant-gardeâ€: namely, to “consecrate the comic book form through a reinvention of its low-culture elements and association with consecrated aspects of modernism.†In the July issue’s excerpt from the chapter entitled “Art,†Gerner holds comics, that most populist of art forms, up to Pop Art, finding the latter wanting and, worse yet, overpriced, exposing not only a long-running hypocrisy in society’s attitude toward comics, but how permeable, even susceptible, disciplines once thought distinct are to each other’s influence. On Gerner’s pages, works of art are imported to the comics realm in deliberately, characteristically cartoonish renderings, as though all comics, or at least Gernerland, were a unified geography, and by going there we ourselves would be Gernerized. At the same time, Gerner abandons the meticulously gridded layout, known in French as the “waffle iron,†that he uses in books like Court-circuits Géographiques and (Un Temps.), thereby liberating the page from panels and sequence, two basic elements often used to define the medium. In pushing the boundaries of a form not usually associated with nonfiction, Gerner creates something like a museum on paper, where art is recontextualized in a comics setting; invited into this contemplative space without prescribed route, the reader’s eye freely saccades from quote to image down pages as much argument as collage.

Take a step back, and the strategy is further complicated: as Beaty notes in his pioneering study Unpopular Culture, comics’ acceptance in Europe was evidenced “increasingly, by the incorporation of comic book art into museums and gallery spaces that had long excluded them.†Published by L’Association (the driving force behind the French alt comics renaissance of the ’90s and ’00s), and active in OuBaPo (the comics equivalent of Oulipo), Gerner was one of several artists, central to the French comics avant-garde, whose work brought about this acceptance. Indeed, Against Comics (Contre la B.D.) is at times so culturally specific in its cultural references, and the fights it picks, that one hesitates to translate B.D. (bande-déssinée) as “comics.†In a global age when beggared English grows by borrowings, it seems useful to be able to employ both freely, and not be misunderstood, much as we already differentiate between comics and manga. New words may be needed to keep up with a medium reinventing itself in distinct cultural traditions around the world, each interrogating their own origins and limits, the better to evolve and astonish.