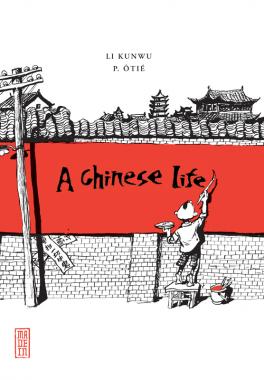

just dropped in stores this month, all 700 pages of it. Originally published in 3 volumes from 2009 to last year, this hybrid of personal and national memoir chronicles what is perhaps one of the most recent and massive dramatic upheavals in global history that most of us in the West still know very little about. And yet the last half-century of China’s development is something that surely affects us all already. As publisher Self Made Hero puts it:

“Li Kunwu spent more than 30 years as a state artist for the Communist Party. He saw firsthand what was happening to his family, his neighbors, and his homeland during this extraordinary time. Working with French diplomat Philippe Ôtié, the artist has created a memoir of self and state, a rich, very human account of a major historical moment with contemporary consequences.â€

In this graphic novel, the modern Middle Kingdom, closed for so long, opens at last to provide a very personal glimpse. Li’s supple technique ranges from echoes of traditional art, flawless propaganda reproductions, and an original, often tortured expressionist style where distortions in face and figure reflect inner turmoil. One of many stunning achievements in art and story is the way he makes palpably credible just how it is so many people thought and acted as one. When the first volume ends with an announcement of Mao’s death, the grief and terror of the populace is one of the book’s most harrowing moments. This trauma is echoed in the second book with the death of Li’s father, a Party official. Despite being interned in a re-education camp for ten years, his last words to his son are, heartbreakingly, no personal message but a political exhortation toward the Party. The personal and political are intertwined in a way we in the West have too long had the perilous luxury of ignoring.

In the third volume, Li and Ôtié pull away from chronicling the history of Li and his family. By this time in Li’s life, he was well established as a unique sort of journalist for the Yunnan Ribao (Yunnan Daily), reporting political and human interest stories via the cartoon medium, or manhua. In an interview with People’s Daily Online, Li says:

“When I was young, I used to leave a brief note to my mother with my own cartoon image instead of words… One morning I drew a little boy holding a bowl and my mom understood that I went out for breakfast.”

Li’s new status in life is reflected as his character becomes more of a narrator, relating how people he’s met and listened to navigate the new, rapidly changing China: a masseuse from the countryside, a bottled water magnate, an elderly factory worker. Fortunes shift overnight, people seem to live multiple lives like in Borges’ “The Lottery in Babylonâ€: one man goes from opening a pool to running a tiny bodega, while another from selling scrap iron to owning a successful restaurant chain, and a third from a militant young member of the Red Guard to living in a cave. It sounds trite to invoke triumphs of the human spirit, but the absolute wringer of daily life in China depicted here is, by any standard, exhausting and traumatic. The sheer abuse, its duration and repetition, is such that any given character’s mere survival proves deeply moving.

Though I’d seen the books prominently featured in comics shops while I was still living abroad, I didn’t really start translating it until the rights were being shopped around to English-language publishers. At the same time, I’d carved an excerpt of it out for Words Without Borders, which appeared in their annual February comics issue in 2011. Working on this book was a unique challenge that called not only on my French, but my limited knowledge of written Chinese. Communicating, via their French and English publishers, with Li and Ôtié during the revision process, I was often triangulating between both languages and English. The proliferation of simplified Mandarin signage in the panels—some translated in footnotes and some not—also greatly enriched the context that informed my word choices. The creators also took this chance to revise some of the book’s content for publication in the language that would win them the widest readership: English. (So far, it’s also been translated into German and Korean—interestingly, both countries with communist histories.)

In a short but very interesting interview with Albert Helly, conducted at the offices of “French Without Borders†in Kunming, Li reveals that he was the first in his family to draw. While the parents of most Western children try to keep their children from scrawling on the walls, there were “no white walls in the neighborhood,†so he drew in the dirt. Through his adolescence, military service, and successive political revolution, “drawing was a joy.â€

He met Phillipe Otié in 2004 through a mutual friend. Ôtié’s wife was the agent for Kana, the manga division of comics publisher Dargaud. Li and Ôtié initially pitched Kana a life of Marco Polo, but editorial director Yves Schlirf was more interested in Li’s own story.

The third volume of A Chinese Life recounts Li’s first visit to France, a mostly silent and comedic section featuring many classic tourist mishaps: guidebooks, dual-language dictionaries, looking for the bathroom, and having to settle for ubiquitous bread when, as Li says, “I wanted rice!†It also tells of Li’s astonishment at the Angoulême festival, where the second volume was an official selection in 2010. One of the book’s main themes is developed: the clash of cultures between Westerners who want to hear dirt dished about China, and Li’s desire to present not only a fair-minded portrait of everday life, but one faithful to his own unsensationalized experience. The first volume made the year’s end 5-title best Asian comics shortlist from the Association of Comics Journalists and Critics, and was chosen as 2009’s representative title for an exhibition at the Centre National de la BD in Belgium. In 2010, the second volume won the Prix Château de Cheverny de la BD Historique 2010 and the Prix Ouest-France du Salon Quai des Bulles.

Li believes he was destined to visit France, since his grandfather spoke of it often to him as a child. The extent of urban greenery surprised him; he’d imagined Westerners lived in a state of “total stress,†deprived of nature’s rejuvenating powers, but realized that Chinese urban development had created a much more stressful environment. He also told Helly that “In China, the government fosters the growth of culture. In France, culture is in everyone, and everyone fosters it on his or her own.â€

A member of the Chinese Communist Party, Li Kunwu is currently an administrator at the Yunnan Association of Artists and the Chinese Institute for the Study of Press Illustration. In his 40-square-meter studio near his home, he is busy drafting new books, continuing the story of a Chinese life. The fourth and fifth volumes are finished, and a sixth is planned. In a career of over 50 years, Li has had thirty-some books published in China, and also pieces in the biggest Chinese comics magazines, Lianhua Huabao and Huma Dashi. Many of his works are almost documentary in nature—narratives of travel, usually by bike, in his native Yunnan province, often among ethnic minorities or in historic districts. A Chinese Life has yet to be published in Chinese.

Leave a Reply